The amateur era: Archery at the Olympics from 1976 to 1992

Four years after archery’s return to the Olympics in 1972, the Games were held in Canada.

After the terrible incidents in Munich, Montreal was peaceful – and it is perhaps best remembered in the public eye for the performances of gymnast Nadia Comaneci, who became the first athlete in her sport to score a perfect 10 at the Olympics.

One of the advantages of outdoor archery when compared to many Olympic sports is that it doesn’t require any permanent infrastructure.

The only essential facility is a flat, outdoor piece of land. This gives organisers flexibility to put the event in many different spaces – often in front of iconic backdrops more recently – and this has likely contributed to the sport’s survival in the Games pantheon.

In 1976, the archery competitions at the Olympics were not held in Montreal itself but in a park in the city of Joliette, 50 kilometres northeast of the main venues. An existing archery range was expanded with spectator stands for 2000 people.

The official report on the venue gives a flavour of the genteel priorities of the time: “…seven small pavilions housed quarters for the hostesses, a results centre, the archery secretariat and [federations]. These small wooden buildings with gabled roofs and ochre-coloured walls were grouped around a small plaza and created a warm and inviting atmosphere at the site.”

Only 64 archers from 21 nations competed in Montreal. The format was the same as in 1972 – the double 1440 Round – and, again, archers from the USA took the gold medals.

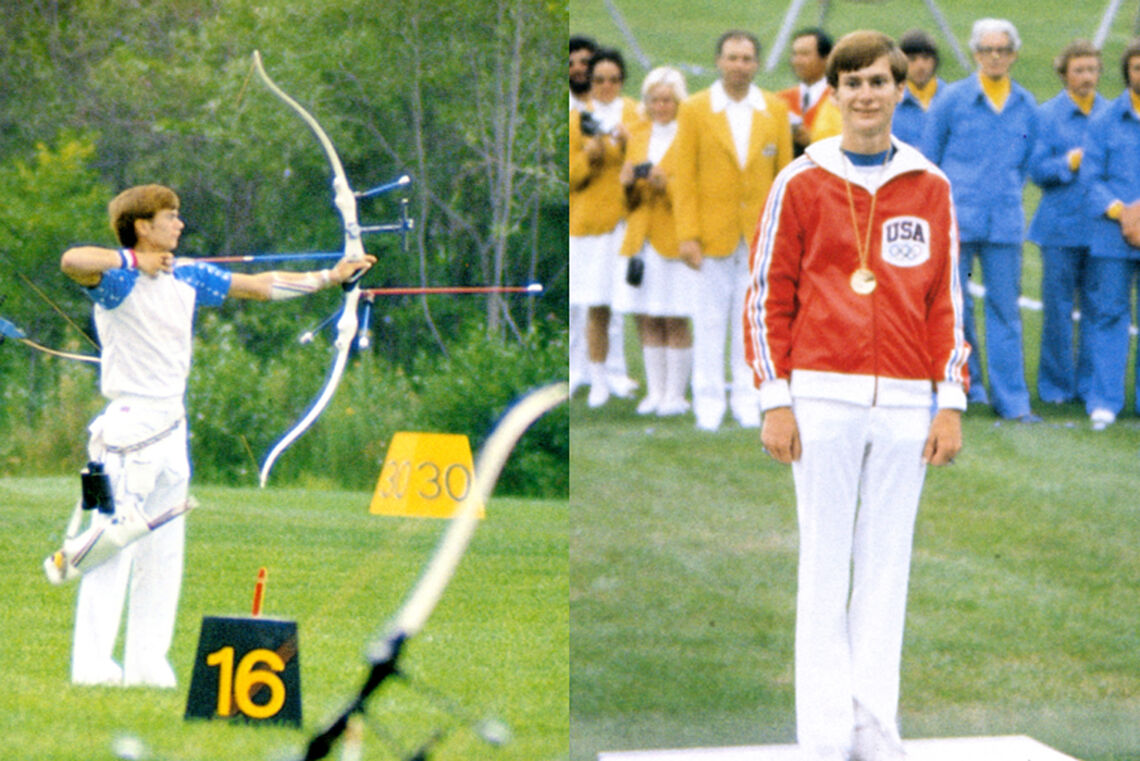

Darrell Pace, who had almost made the US team as a 15-year-old in 1972, collected the first of his two individual Olympic victories in Canada. He destroyed the field, setting a new world record of 2571 points in the process.

“There’s a feeling that lasts for a minute,” he said of standing on the Olympic podium. “But what a feeling it is, to know that you are the best in the world at what you do.”

The women’s competition was won, somewhat out of the blue, by Luann Ryon with a total score of 2499 points.

Just 23 years old, she had only entered a single US championships before winning the Olympic trials for 1976, and the Olympics was her first international competition. Ryon would go on to win the World Archery Championships in 1977 and medals at the Pan American Games in 1983. However, despite trying many times until the late 1980s, she never made another Olympic team.

In 1977, the late Francesco Gnecchi-Ruscone took over from Inger Frith as the president of FITA when Frith retired.

Francesco, a successful architect and president of the Italian federation, inherited a different organisation from the one today. While the return to the Games had increased the number of active countries in the modern sport of archery, FITA was still not a large affair.

“I think it had about 30 member associations of which perhaps 20 were active,” said Francesco, speaking in 2017.

“The effect of becoming an Olympic sport immediately raised the number of member associations but Mrs Frith had been running FITA as a small club in fact, partly because of her way of seeing it, partly because of her autocratic character and partly because there was no money.”

Unfortunately, something in the succession process had upset Frith. During the official handover, in a Heathrow hotel, Frith refused to give Francesco any files or archives relating to the two decades she had been at the head of the organisation.

He was forced to return to Milan and essentially rebuild the organisation from scratch.

“I never understood why, I’m sure she had nothing to hide. She had in fact a very positive presidency with the acceptance of archery on the Olympic programme. She should have been very proud of handing over the files,” said Francesco.

Working closely with Giuseppe Cinnirella, who would become secretary general, FITA began a long period based in Italy and closely associated with the Italian federation. The two men would shape archery’s future for decades to come, setting foundations for the sport’s evolution into professionalism at the turn of the millennium.

The Olympic situation in 1976 was not settled.

“I was working very hard within FITA to strengthen our position in the Olympic world, which was positively weak,” said Gnecchi-Ruscone. “Had there been any need for a reduction of the Olympic programme, we would certainly have been among the first out.”

A decade of careful politicking was required to deal with national federations, many of whom, in the eras of both apartheid and hardline communism, refused to be at the same competition as one another.

Part of the problem was the Olympic movement itself was in crisis. Some 66 nations, including the United States of America, boycotted the Olympics outright in 1980 in protest at the Soviet-Afghan war.

The boycott meant that Darrell Pace would be unable to defend his Olympic title from Montreal.

At the time, he was undoubtedly the number one archer in the world – his scores for the 1440 Round (then-FITA) were said to be more than 100 points higher than the eventual winner.

Even worse, as a member of the air force, the usually outspoken Pace was unable to make his frustrations known because it would go against the orders of his commander-in-chief.

“No comment, no comment, no comment,” Pace recalled. “That’s all I could say because I was in the military.”

Pace – not a man short on self-confidence – later claimed that he would have been “pretty much guaranteed” gold. He put down his bow for the rest of the year, and considered retiring, but changed his mind shortly afterwards.

The absence of Pace and Rick McKinney in 1980, as well as the best competitors from Japan, opened up the men’s competition in Moscow. Archery was held at the Krylatskoye Sports Complex, a few kilometres west of Moscow, next to the canoeing and rowing lake.

(The spectator stands are still in place but the archery field is now a track for dirt bikes.)

For the first time, electronic scoring and timing systems were used on the competition field.

The Soviet Union was an archery powerhouse at the time and the team was expected to sweep the podium in the absence of the US. However, on the third day of competition, an unknown 18-year-old called Tomi Poikolainen from Finland surged ahead from fifth place to take the lead.

He held his nerve on a rain-lashed final day to finish with 2455 points and victory by just three over Boris Isachenko of the host nation. He was, and remains, Finland’s youngest gold medallist at the Olympics. Poikolainen went on to a long, successful archery career that took him to five Olympics and a European title in 1986. He also took an Olympic silver medal with the Finnish team in 1992.

The women’s title was won by Keto Losaberidze from Georgia, which was then part of the Soviet Union. She had placed fourth in the Olympics in 1972. Losaberidze is archery’s only Soviet Olympic champion.

In 1984, the Games went back to North America. Los Angeles 1984 is now seen as a pivotal, ‘game-changing’ moment in Olympic history. The use of existing venues and private funding meant the Olympics became profitable for the first time – contrasting sharply with the Games in Montreal which were a widely-publicised financial disaster.

A record 140 nations took part, 35 in the archery competitions.

LA was the first Olympics to be widely covered by television and the first Games at which the rights for broadcast became a major source of revenue for the international federations.

“Until then, the IOC attitude to television was rather, ‘we are grateful for you to come and show our Games’,” said Francesco. A third of the television rights revenue was split equally among the federations and, for the first time, FITA had money to begin developing the sport.

El Dorado Park in Long Beach, nearly 30 kilometres southeast of the Olympic stadium, welcomed 109 archers for the archery events in LA.

As in Montreal, an existing club was expanded for the competition, this time with seating for 4000 spectators. (The field remains a working archery club today.) No Olympic village was built for the Games in Los Angeles and archery teams stayed in the halls of residence at the local university – UCLA.

The production was not without teething problems.

“For the first time during the shooting, [we] had a live commentator on a microphone,” said Francesco. “It had never happened before but anyway it was one step forward. Even so, the poor man didn’t know what to say because he also had to wait for the scores to appear on the board in order to talk about them and by then everyone was already six arrows ahead.”

A tit-for-tat boycott saw Soviet athletes absent from the 1984 Olympics but one nation that had been absent from Moscow made its Olympic archery debut: Korea.

From the 1970s onwards, Korea had focused money and effort on less-popular Olympic sports. With a bid in for the Olympic Games in 1988, there was a concerted effort to produce athletes who would, in turn, produce medals on home soil.

Informed by a traditional archery culture and a disciplined, quasi-military approach, the arrival of the Koreans to the international scene had not flown under the radar. The recurve women’s team had already won the world championships in 1979 and 1983.

Park Young Sook – known as Sally and later a national coach in Italy, Malawi and Bhutan – competed for Korea in Los Angeles, finishing 17th.

Her compatriot Seo Hyang-Soon, aged just 17, took gold to become the country’s first-ever Olympic Champion in any sport. Kim Jin-Ho, also of Korea and the reigning world champion arriving in LA, collected bronze with Li Lingjuan of China in second place.

Although the men’s event was still dominated by the top US archers, a new Asian-focused chapter was beginning on the women’s side of the aisle.

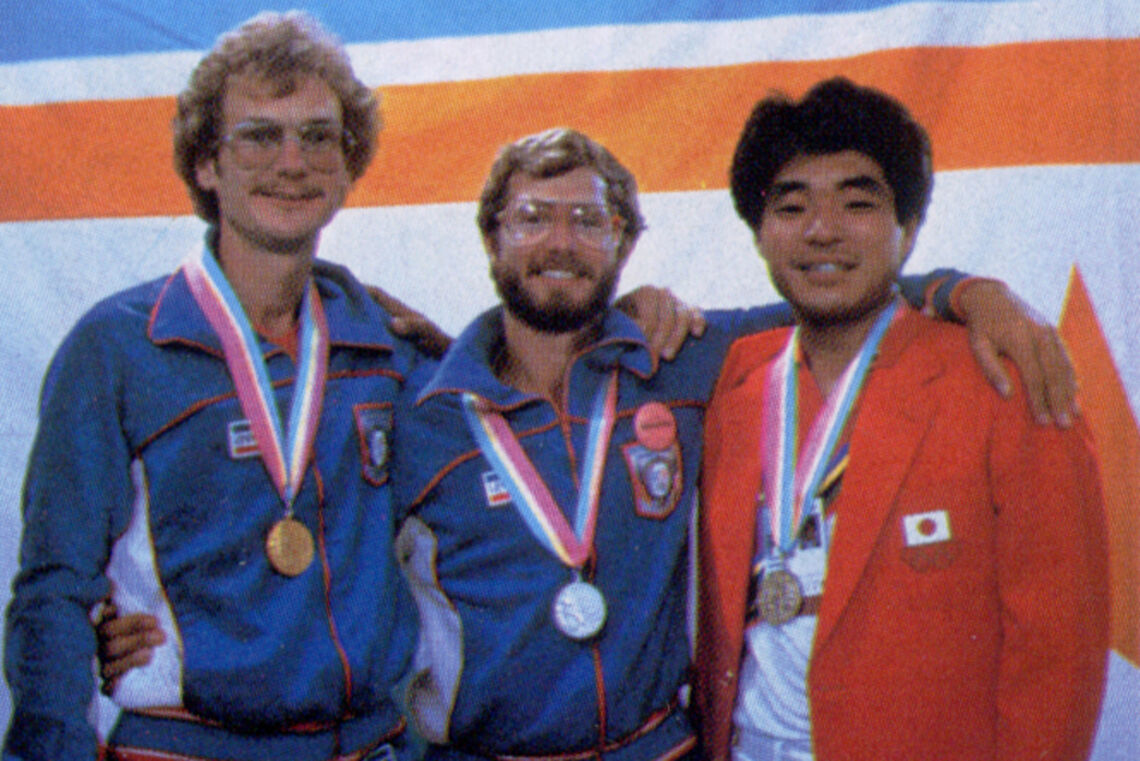

The event in Los Angeles was preceded by a World Archery Championships held at the same venue in 1983. There, Rick McKinney had snatched the title from favourite Darrell Pace on his very last arrow. In that era, the two men dominated the international archery scene.

“You wouldn’t believe how many times Darrell and I would show up to a tournament, and the first thing that would come out of peoples’ mouths was, ‘well, looks like we’re going for third place’,” said Rick in 2021.

Fireworks were expected at the Olympics but, in the end, Pace led from the front and never looked back.

Thirty-five points ahead by the end of the second day, he finished with a new Olympic record of 2616 for the double-1440 Round, a full 52 points ahead of McKinney, who just beat Japan’s Hiroshi Yamamoto to the silver medal with his last arrow.

Pace remains the only archer to have won the individual Olympic competition twice.

Pace and McKinney would return to the Olympic team in 1988, although that would be Pace’s last appearance.

In 2011, as part of World Archery’s 80th anniversary celebrations, Pace would be declared the male archer of the century for his unique achievement of becoming Olympic Champion twice.

When the Games of 1988 were awarded to Seoul in 1981, it echoed the narrative of Japan hosting the Olympics in 1964 – a nation recovering from a devastating war and emerging again into the world. In truth, the Korean bid itself was actually made by a military dictatorship intent on displaying power.

But by the time the Olympics actually happened, after a decade of civil unrest, a fragile democracy had emerged.

The archery competition was held on a field at a military academy called Hwarang, then and now used for training Korea’s army elite. Most importantly from a sports perspective – the format had changed. For the first and only time at an Olympic Games, the Grand FITA round was used.

It was the first foray into making archery more spectator friendly.

After a single 1440 Round used as qualification, the scores were reset and the top 24 men and women shot the four distances again but this time only nine arrows, rather than 36, at each. A further six archers of each gender were then eliminated and the remaining 18 shot the nine arrow rotation again.

Further cuts to 12 and then eight, for the final, followed as the process was repeated.

The impetus for changing the round came from Francesco and Beppe. On their way back from the Olympics in Los Angeles, they had “decided that the double FITA round was going to kill FITA… [it was as] interesting as watching paint dry”.

The pair was determined to deliver a competition that would appeal better to an audience. But they also needed something that would be acceptable to skittish national federations, most of whom were strongly wedded to the four-distance FITA, which had been the standard since 1956.

Ultimately, the Grand FITA was the compromise.

“We were divided between the wish to be creating something entirely new and the need to go prudently,” said Francesco. They tested the new format in Italy – with success.

“With the old double-FITA round, all you needed was regularity and stamina… at the end of the first round that is at the beginning of the third day, you already knew that it was a competition at most between three or four people. Here you needed initiative, quick reaction to a ad arrow and much more fighting spirit.”

The number of medals available at the Olympics had also suddenly doubled. For the first time, there was a team round, based on the same concept, with 12 teams entering the first elimination phase and a cut to eight for the final.

In the end, the Grand FITA only saw action at the world championships in 1987, 1989 and 1991 as well as in Seoul in 1988. However the goal of making archery more spectator friendly would remain, being realised with the introduction of head-to-head matchplay in the years to come.

Jay Barrs took gold over Park Sung-Soo of Korea in Seoul, meaning that four of the first five men’s Olympic Champions in the modern era were from the USA.

In the women’s event, Korea swept the podium with Kim Soo-Nyung – often regarded as the greatest Olympic archer of all time and still at the top of the all-time individual medal table – taking gold ahead of teammates Wang Hee Kyung and Yun Young Sook in second and third.

Speaking in 2016, Soo-Nyung said she “could see the gold medal coming”.

“On the last round, I shot nine arrows at 30 metres and got a perfect 90 points. I felt confident and got better and better. Once the target moved to 50 metres, I shot six of the nine arrows in the 10,” she recalled.

(The order of the distances was inverted, shortest to longest, for some Grand FITA elimination passes.)

“I set-up again, and was on my game and so confident that again, it just went 10-10-10…”

It was clear that things were being done differently in Korea. Part of the training instilled an absolute lack of self-doubt, a self-confidence that other nations could only dream of. Remarkably, the Korean women in Seoul were all teenagers, aged just 17, 18 and 17.

The day after Soo-Nyung’s win, all three returned to shoot the team event.

The result was unambiguous. Korea won gold by 30 points, with Indonesia in second and the USA in third. The Olympics in 1988 brought the first in an unbroken sequence of women’s team victories that perseveres to this day, becoming one of the greatest active winning streaks in Olympic history.

Korea would also win the men’s team title, relegating the USA into second and overshadowing what should be regarded as one of the greatest squad line-ups in history: Barrs, three-time individual world champion McKinney and Pace, still the only archer to win two individual Olympic titles.

In Seoul, the game changed – permanently.

Barcelona 1992 was another Games that was transformative – but this time for a city, rather than a nation. An eccentric provincial port town became a great world city almost overnight. The world had also changed; the Berlin Wall had fallen, the Soviet Union had broken up and athletes in 12 former Soviet republics competed as a ‘Unified Team’.

The women’s squad, consisting of Natalia Valeeva, Khatuna Lorig and Ludmila Arzhannikova would take bronze.

All three would eventually leave their home nations and compete for other countries at subsequent Games: Valeeva for Italy, Lorig for the USA and Arzhannikova for the Netherlands. (Valeeva won individual bronze in 1992, too.)

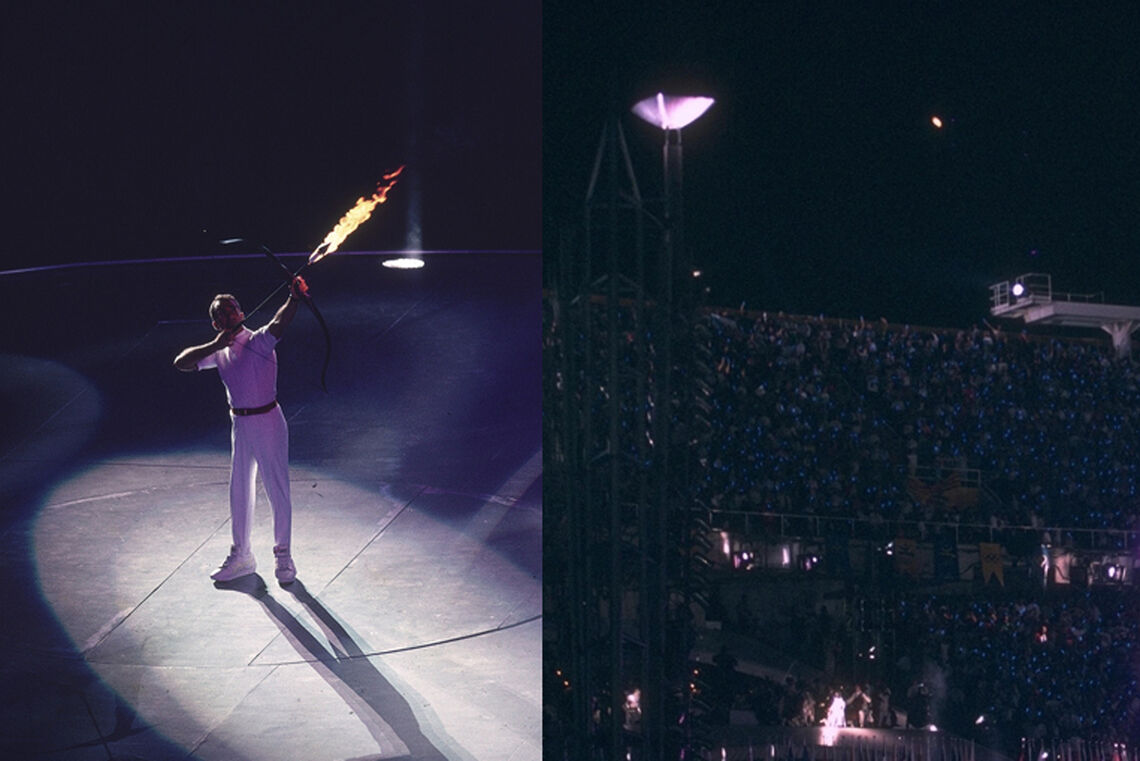

One of the more iconic moments for archery at the Olympics occurred before the competition got underway.

At the opening ceremony, Paralympian Antonio Rebollo lit the Olympic cauldron with a flaming arrow. A native of Madrid, he had been reluctantly chosen by the organisers just moments prior to the event itself. (He never signed a release for the use of his image, due to the last-minute call-up, causing later headaches for the institution.)

Rebollo apparently used a bow with a draw weight of 72 pounds for the shot, which was needed to launch the heavy arrow 69 metres to the target. The lit flame also obscured his view and he used a stadium spotlight as a reference.

“There were no fears. I was practically a robot. I focused on my positioning and reaching the target,” he said afterwards. “My feelings were taken from the people who described to me how they saw it. What they felt, their emotions, their cries. This is what made me realise what the moment actually meant.”

The shot was perfect. (No, it wasn’t meant to land in the cauldron. He’d already destroyed one during practice this way.) It became widely recognised as one of the most memorable – and perhaps, risky – moments of any Olympic opening ceremony, perfectly capturing the spirit of Barcelona and the Catalan character of rauxa, which is usually translated as ‘madness’.

It’s been suggested that is the most-viewed archery shot in history.

Rebollo was immediately sent back on a train to Madrid. He would return a few weeks later to win a silver medal at the Paralympics (the third podium of his career). The actual arrow that lit the Olympic cauldron remains, mysteriously, missing.

On the archery field, for the first time, the Olympic competitions used a head-to-head matchplay bracket at 70 metres, although qualification remained the four-distance 1440 Round.

The top 32 archers and top 16 teams in each category were seeded for the knockouts. This was long before the invention of the set system, so the result of all matches was decided on cumulative score, 12 arrows for individual and 24 arrows for the team events.

In a temporary venue to the west of the city, 136 archers from 44 nations competed for five days.

Spain took a surprise home victory in the men’s team event (after the three individuals qualified just 29th, 42nd and 45th), beating Finland by two points in the final. It remains the country’s only Olympic medal in the sport and one of archery’s biggest Olympic upsets.

The day prior, the national newspaper El Pais printed a list of the upcoming competitions. It read: “Archery – medal chances, none”.

Spain’s king witnessed the eventual victory, jumping over from the nearby tennis venue when he heard the team was in the final. The timing was right for the rest of the country, too.

“It was lunchtime, so everybody in Spain had the TV on to watch archery,” said Juan Carlos Holgado, a member of the squad who would go on to organise the archery events at the Athens 2004 Olympic Games and work for World Archery for nearly two decades.

Frenchman Sebastien Flute won the men’s title in Barcelona, defeating all three of the Korean men’s team along the way. (Flute’s story continues to this day, as he prepares to organise the archery events at the Paris 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games.)

In the women’s competition, Cho Youn Jeong of Korea beat her compatriot and defending Olympic Champion Kim Soo-Nyung to the individual title.

Archery was becoming professional. But it wasn’t there yet.

In a stark reminder that the vast majority of athletes were not full-time, an unemployed roofer – the late Simon Terry – took individual bronze, becoming Great Britain’s first individual archery medallist since 1908 and the pre-FITA era.

(When he returned home, he found that his benefits had been cut off because he had made himself unavailable for work.)

Great Britain, and many other countries, would gradually begin pumping huge amounts of government money into Olympic sport. The Games themselves would rapidly become a commercial vehicle of unparalleled proportions. And, soon, FITA would no longer be run by volunteers – but employ staff.

The amateur era was over and the Olympics were getting bigger than ever.

Professionalism was just around the corner.

This article is dedicated to the memory of the former president of World Archery, Francesco Gnecchi-Ruscone, who contributed so much and passed away just before it was published in September 2022.