Hitting unseen stars: The history of Korean archery

We all know how seriously archery is taken in Korea as an Olympic sport. But: why archery? Why that sport, and not another?

The answer lies in a complex web of history. For much of the last thousand years, the Korean peninsula was called Joseon, and it was ruled by a long-standing imperial dynasty from the 15th to the 20th century.

This deep-rooted tradition continues today, as Korea prepares to host the Gwangju 2025 Hyundai World Archery Championships and the Gwangju 2025 World Archery Para Championships in Gwangju.

Archery in the Joseon dynasty was not only a military skill but also a cultural, spiritual and scholarly pursuit, carrying deep symbolic as well as practical value in Korean society. It remained so throughout an era marked by significant advancements in science and technology, and a strong intellectual culture influenced by Chinese traditions and Confucianism.

The taste for archery was set at the top. Many of Joseon’s monarchs were said to be masters of the sport. King Jeongjo (1776-1800) often displayed his skill with the bow and was described by one flattering account as “unrivalled by his contemporaries.” While practising at Suwon, he was reputed to strike the target 24 times out of 25.

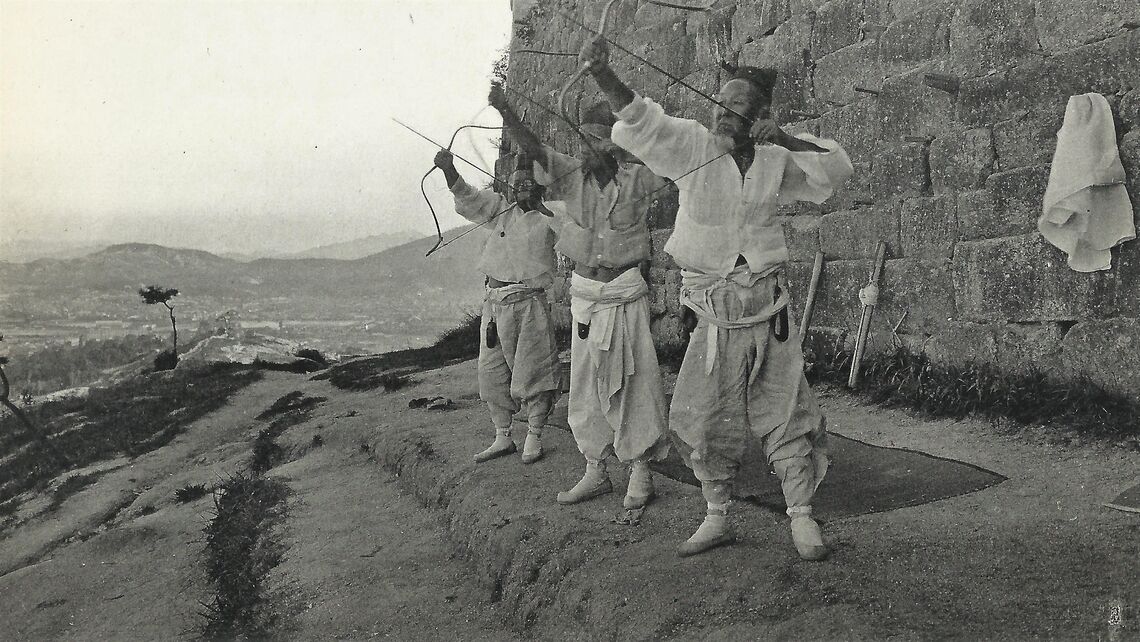

Before the widespread adoption of firearms, archery was also the backbone of Joseon’s military forces. Korean archers were famed for their skill with the gakgung, a small but powerful composite bow made of horn, sinew, bamboo and wood – a highly refined version of older Asiatic composite bows. Even as gunpowder replaced bows, the gakgung remained highly valued for centuries for its range, accuracy and rate of fire.

In one of many technical innovations of the age, Korean armourers added a pyeonjeon, or grooved firing tube, which increased the range of the arrow, and developed the fire-arrow organ gun known as the hwacha, capable of firing over 100 arrows simultaneously.

It was not an entirely male world. During wartime, women helped construct both bows and arrows and apparently also manned the city walls of Seoul with small bows firing fifteen-inch “iron arrows, like a needle, with great force.”

Archery had also become an integral part of elite Korean society. According to Shin Myung-ho, author of a book on Joseon royal court culture, it was “a fundamental aspect of refinement.” A document called the Daesarye Uigwe (Royal Archery Rites) from 1743 details a revived ceremony in excruciating detail, reflecting an age obsessed with ritual.

The Joseon kings held these rituals at Songyongguang, an academic institution for training government officials. According to the KNCU:

With the eyes of everyone on him, King Yongju took his place on his shooting platform. When the king pulled his bowstring taut, three phrases of music were played. And when he released his arrow, another four were played... If an arrow hits the mark, a drum sounds. If it misses the mark, a gong sounds. From behind the screen fence to the east of the targets, people holding flags of six colours announce where the arrows hit...”

Prizes for the great and good in attendance included clothing and bows, while a penalty for missing was a shot of alcohol – suggesting this particular meet was not the most serious competition. But it is clear that under neo-Confucian influence, archery became associated not only with warfare but with civic pride, moral cultivation – and, crucially, social advancement.

Archery remained a prestige activity for centuries and was still part of civil service examinations until the late 19th century.

Later, Westerners also witnessed archery events in the country. The English painter and writer Arnold Henry Savage Landor visited Seoul in 1891 and wrote about what he saw, including archery, which he described as one of the few sporting events in Korea:

“Princes and nobles indulge in it, and even become dextrous at it. Nevertheless, the noble’s laziness is, as a rule, so great, that many of this class prefer to see exhibitions of skill by others, rather than have the trouble of taking part in such themselves; professional archers, in consequence, abounding all over the country, and sometimes being kept at the expense of their admirers... Both the Government and private individuals offer large prizes for skilful archers, who command almost as much admiration as do the famous espadas in the bullfights of Spain. The King, of course, keeps the pick of these men to himself; they are kept in constant training and frequently display their skill before his Majesty and the Court.”

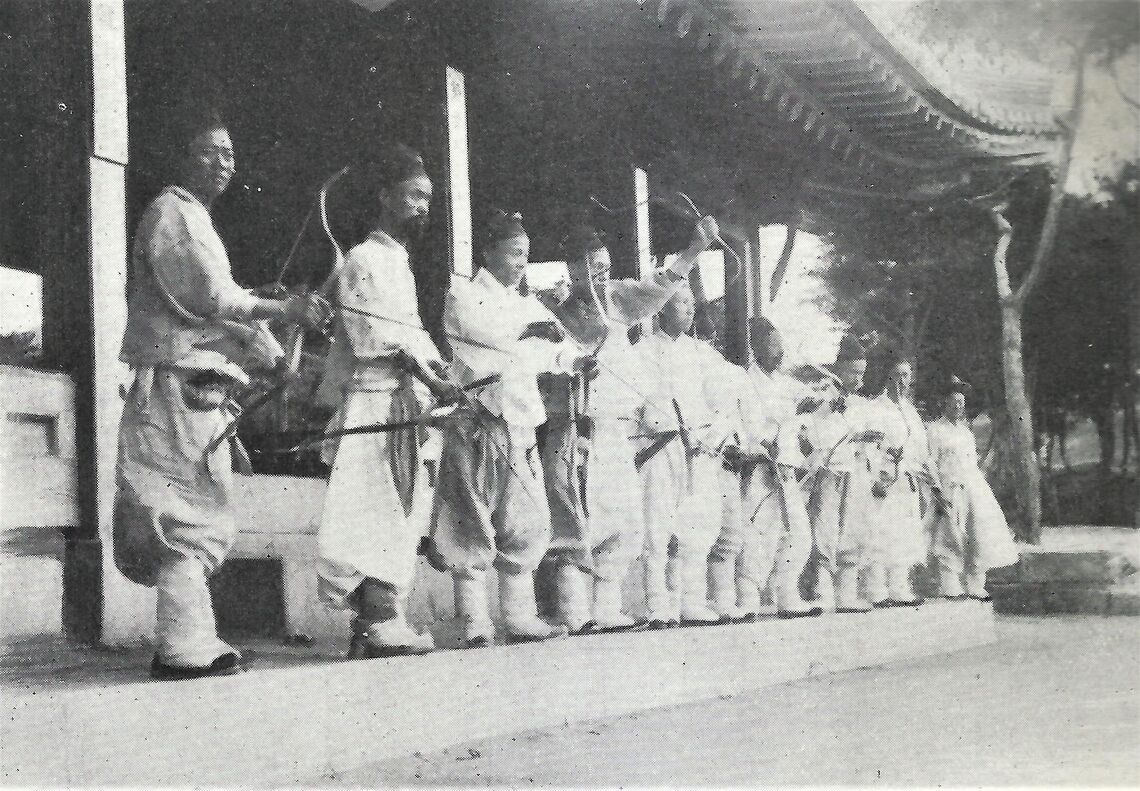

The American traveller Burton Holmes visited Seoul at the end of the 19th century, spending “an interesting hour watching the gentlemen of Seoul contending in friendly rivalry in the dignified and medieval exercise.”

He went on to describe a genteel-sounding, newly established archery range:

"...a temple-terrace for the archers, the target on a terraced hillside, beyond a broad green-clad depression where passers-by may walk in safety beneath the high curvings of the feathered shafts, for the Korean gentlemen aim high, as if intent on hitting unseen stars. And they are accurate of aim; for nearly every arrow as it descends from the cleft skies strikes the mark or, at the worst, falls very near it.”

American ethnographer Stewart Culin also wrote about Korean archery in the early 1890s. According to him, Seoul was divided into four quarters, each with its own archery team made up of men called han-ryang. Culin characterised the han-ryang as “unoccupied fellows,” neither nobles nor soldiers:

“They do no work, but travel from place to place, always carrying their bow and arrows, indifferent to public opinion, and doing whatever they please, and are said to think and talk of nothing but arrow-shoot from morning until night.”

Culin’s account is just one of many historical records describing archers around the world as dissolute outsiders in one way or another.

Seoul’s four archery teams were each identified by a banner: the eastern team bore a green banner; the western team, white; the northern team, an azure banner, generally composed of “noble youths”; and the southern team, red, recruited largely from the sons of military families.

Competitions similarly ended with feasts, drinking and carousing, and the contests even had a kind of cheerleading team of singers called gisaeng.

In some ways, these grand occasions mirrored the heyday of archery among the English aristocracy in the 19th century, with a similar purpose: to entertain, display skill and gamble, with sport as a secondary concern.

By the 20th century, the han-ryang and their world began to seem out of date as the Joseon dynasty drew to a close, although the patronage of archery teams was revived in modern Korea as a way of funding Olympic sport – with great success.

Archery quietly continued as a sport on ranges now spread throughout the country, shooting at a distance of 145 metres, the distance specified in a Joseon-era military exam. These ranges are built on all types of terrain, including ponds, rice paddies, tree groves and even ocean inlets.

Most are membership clubs operating somewhere between a martial arts dojo and a golf club; it remains a sport for the well-to-do. As of 2025, there are 12 registered archery clubs in Seoul and 88 nationwide.

Visitors will notice that the architecture of the jung gahn, or clubhouse, often resembles the grand palaces of Seoul, right down to the identical colour scheme, said to symbolise a tree. There could be no more direct expression of the sport’s royal, dynastic and military heritage.

Archers are expected to bow to the clubhouse when entering and leaving the range – a nod to a time when archery was, quite literally, the sport of kings.

As archers progress up the ranks, they must also use a traditional gakgung bow and bamboo arrows, now crafted by a dwindling number of traditional bowyers, exactly as archers did half a millennium ago.

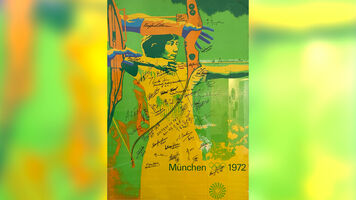

Traditional archery also influenced modern Olympic history. In the 1970s, when the government began investing in Olympic sport, the top traditional archers joined the nascent coaching programme, and some credit the modern, biomechanically aligned Korean recurve style to traditional Korean archery.

The world championships held in Gwangju are merely the latest episode in a tradition spanning over a thousand years.

With thanks to Robert Neff.